Words Leak Out – Found Photographs and Found Poems

This series is motivated by my long-time interest and fascination with the written word. In college I pursued a minor in English and it was then that I first started experimenting with found poems and the cut-up methods made famous by William Burroughs and Brion Gysin.

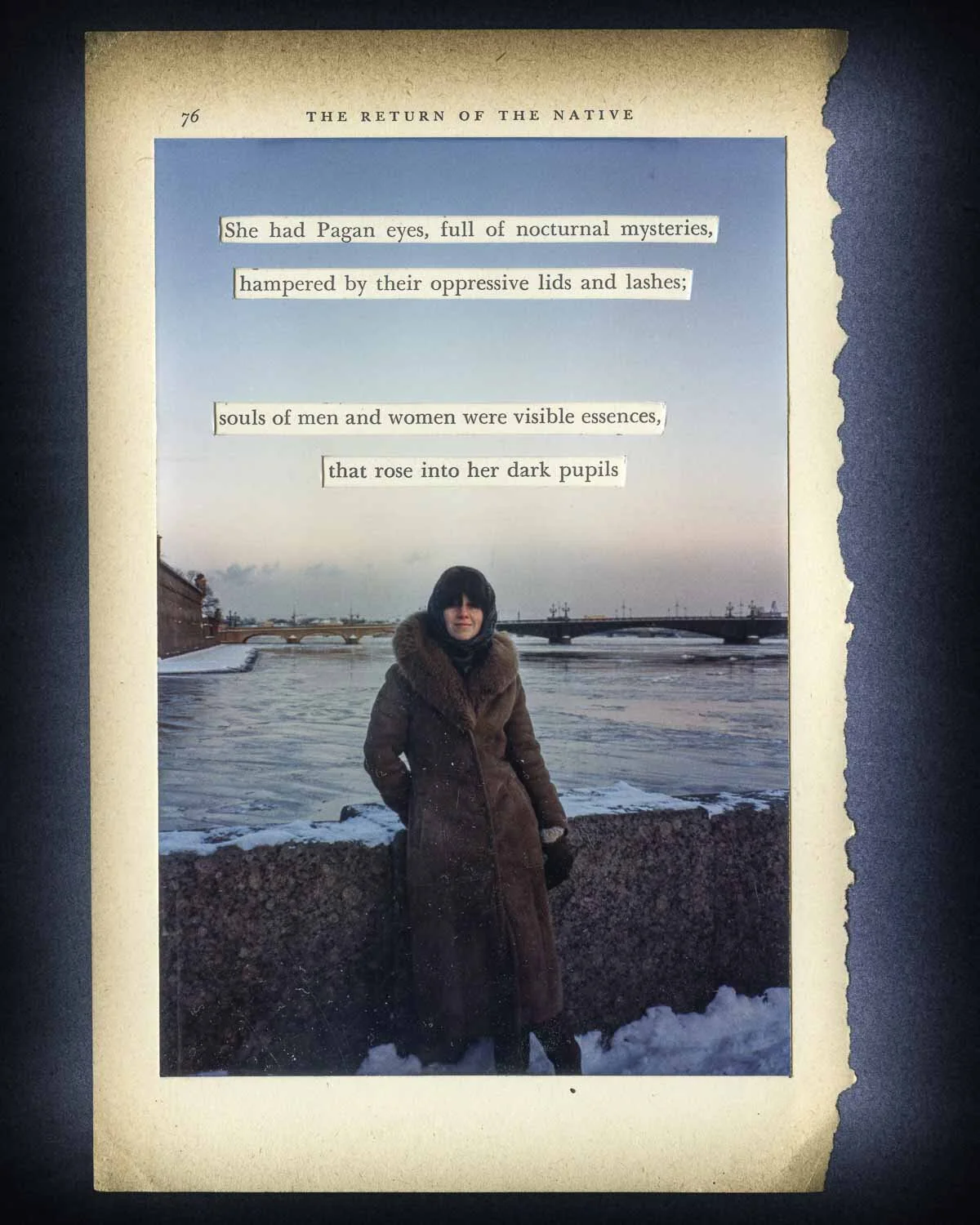

My most recent foray into this realm started while going through my mother’s ephemera after her death – transcribing correspondence, sorting through her many bins of photographs. I could not help thinking about this trove of material as fodder for my art.

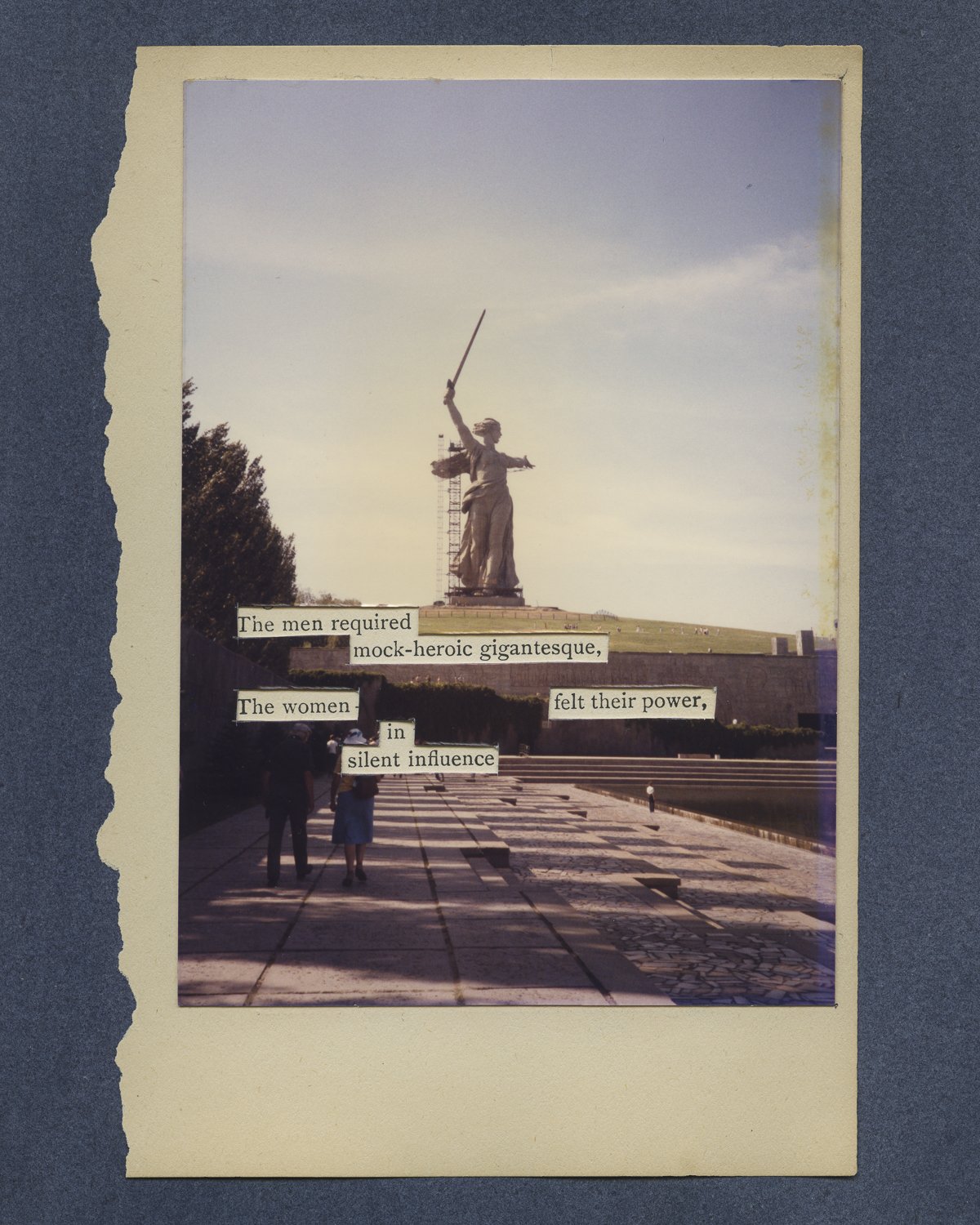

And so, I began working on my own variation of black-out poetry where I place a snapshot over a book page and cut to reveal selected words on that page, creating a poem. I paste the two together creating a new, one-of-a-kind object. The process is not random. I carefully consider and select the passages and images. I have an open-ended conversation with the source materials without knowing where it will go or where it will end, staying open to free-association, flipping back and forth between my sources and my imagination until something sticks.

Early on, I noticed that shorter verses work best in this context, and this led me to investigate haiku as a poetic form for this work. All I knew of haiku came from grade school: an unrhyming, three-line verse of five, seven, and five syllables. I was determined to learn as much as I could about the history of haiku and eagerly trotted off down that rabbit hole where I discovered a whole world of Japanese, short-form poetry: Tanka, Renga, Hokku, Haikai, Senryu, and Haiga. I discovered a long tradition in China and Japan of pairing images with verse in one-of-a-kind works of painting and calligraphy. Although my poetry has been strongly influenced by these traditions, I stop short of including my poems in these traditional genres, rather my poems result from the intersection of these traditional forms with writing techniques pioneered by Brion Gysin, William S. Burroughs, and Tom Phillips, and the surrealists’ and Dadaists’ use of found and appropriated materials.

My poems are not so much composed, as discovered and collected like rare moths. I am the collector searching for just the right combination of picture and words and, in the process of collecting, destroying both the book and the photograph.

In my upbringing, books and photographs were treated as special objects. To take these precious items and destroy them in the making of something new is, for me, revolutionary, iconoclastic, even subversive. I mount each one-of-a-kind poem in a shadow box with pins like that rare moth, displayed as a cherished, collected object. This meticulous and reverent presentation is, in part, a reaction to my discomfort in sacrificing books and photographs in the service of art.

Each one-of-a-kind poem is mounted in a shadow box with pins like a rare moth.

This project started while I was in isolation because of a world-wide pandemic and spending far too much time in front of my computer screen. The purely physical aspects of this work are a welcome antidote to excessive screen time. Cutting and pasting aren’t just a convenient user interface metaphor, but actual physical acts with multiple sensory inputs – the smell of old books, the sound of the pages as I leaf through them and ultimately tear them out, the friction of the blade as it slices through the slick surface of the photograph. It is refreshing to work with my hands, not just a mouse and keyboard.